Politics has changed drastically these last few decades in so many drastic ways, it’s tempting to pinpoint one or the other as the secret to a candidate’s success or failure: For Obama it was allegedly the use of social networks, for Trump it was supposed to have been his use of spectacle to dominate the media narrative, etc…

One thing that is clear, going back to Teddy Roosevelt’s use of the whistle stop, FDR’s mastery of radio, Kennedy’s understanding of television, great politicians have always met the voters where they are, not where they want the voters to be.

It made sense for Ronald Reagan to spend heavily on television ads in 1984, when voters’ eyeballs were glued to their television screens. Now that more Americans pay for streaming services than pay for cable TV, it makes a lot less sense.

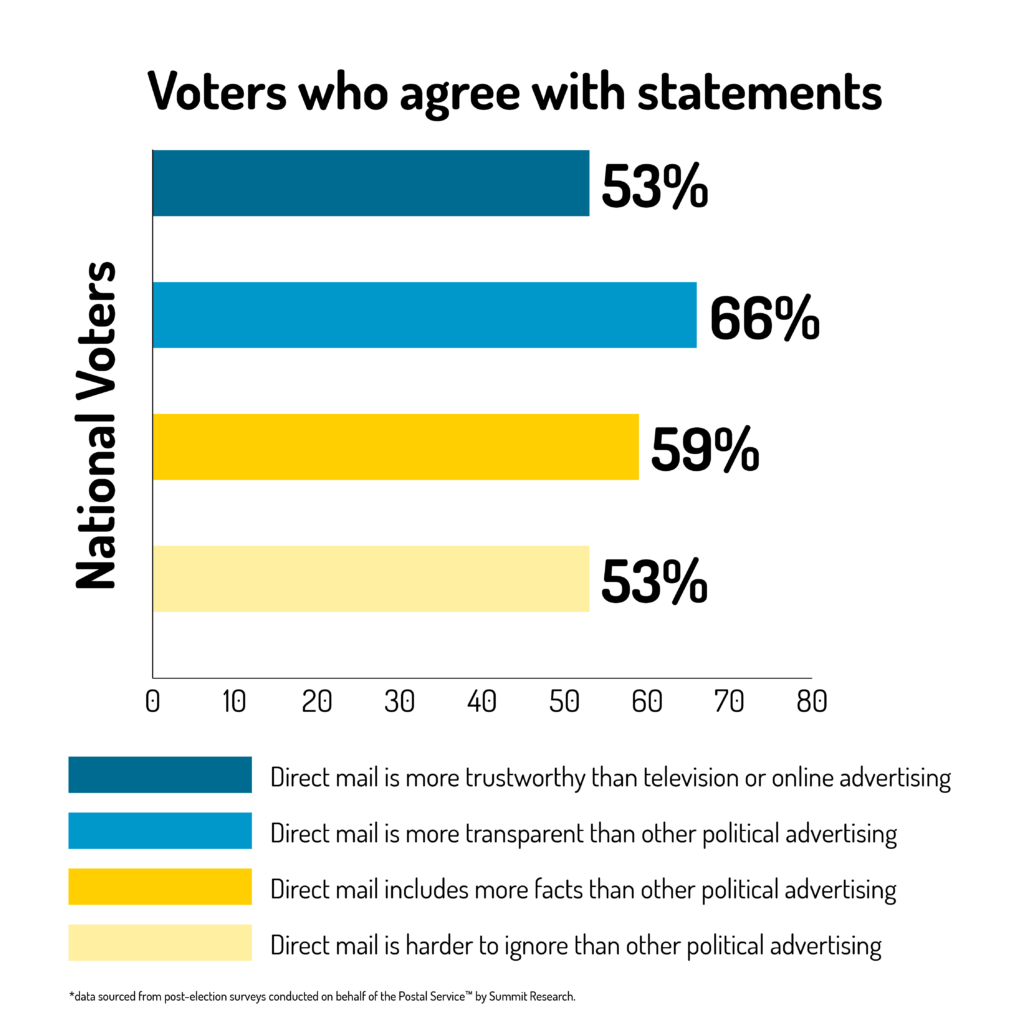

While campaigns in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s were dominated by TV ad spends, massive phone banks with thousands of volunteers and paid callers relentlessly dialing the home phone numbers of every voter, and the battle for newspaper and magazine endorsements, those are no longer attractive places to spend money.

Home phones are an anachronism for many voters, as are newspaper subscriptions. Email addresses and cell phone numbers are hard to come by, and most political emails are automatically filtered as spam, summarily ignored, or quickly prompt the recipient to unsubscribe.

One technique that has been a staple of campaign politics for over a century continues to prove effective, and that is the door knock.

There is something powerful about a candidate or volunteer knocking on your door and asking you for your vote.

They are coming to you, physically, and taking the time to meet you personally and ask for your support. It is impossible to hang up on them (short of slamming the door on them, which almost never happens), or to send their message to the spam folder without hearing them out first.

That is why the days immediately following a door knock are the days when your message is freshest in the mind of voters, and the perfect time to follow up with a handwritten letter.

This is a process that Postalgia can automate for you, so that after you speak with a voter, a letter is written and mailed to them, based on a template, using the data from your CRM, list, or database. It’s a great opportunity to connect on a meaningful level, and you want to make the most of it by employing some of these tips for a powerful follow-up mailing to your voter.

Reference specifics:

Let them know that you’re writing to them after speaking with them, not just mailing them the same thing you mail everyone. Use their name and reference your conversation. Changing “Dear voter, it was a pleasure speaking with you.” to “Dear Karen, it was a pleasure speaking with you at your home on Acheson Ave on Thursday” can be done automatically by pulling details of your door-to-door canvass from your CRM

Change it up based on their support

Did they tell you that they were going to vote for you? Thank them and remind them that their vote is important. Tell them to reach out if they have any questions, or if they’re willing to volunteer or help out with a donation.

Did they tell you they were undecided? Take the opportunity to persuade them. Give them a few words on why they should vote for you.

Did they say that they were not going to support you? Thank them for their time and encourage them to reconsider. Maybe meeting you and getting a nice handwritten note from you will persuade them to stay home.

Whatever they indicated as their level of support, you should be asking for something.

If they’re against you, you’re asking them to reconsider voting for your opponent.

If they’re not sure or would rather not say, you’re asking for their vote.

If they’re voting for you, you’re asking them to take a lawn sign, to volunteer, or to make a donation.

Invite them to reach out

Just as you don’t want your brief conversation at their door to be your last interaction, you don’t want your letter to be the end of the conversation.

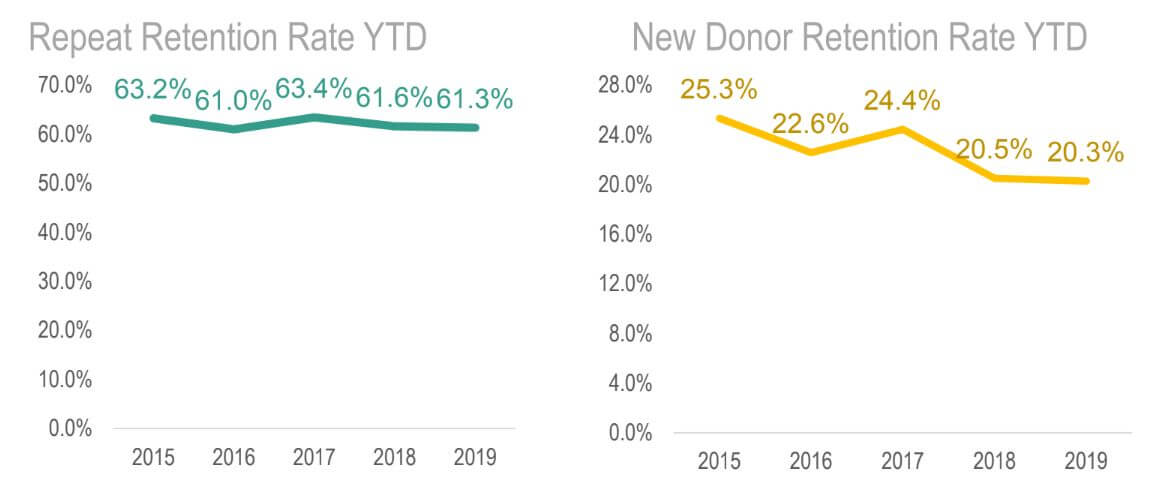

You want to turn your undecided voters into supporters, your supporters into enthusiastic endorsers, and your endorsers into activists.

The best way to do that is by inviting them to be in touch, via their preferred method of communication, to answer their questions, and help get them more plugged in to your campaign.

Whether it’s for an answer to a policy question, a ride to the polls, a sign on their lawn, or information on how they can donate to your campaign, you want them to have a way to reach you.

Great campaigns reach voters where they live, metaphorically and literally. For as long as modern campaigning has existed, that has meant reaching them at their doors and in their mailboxes.